|

My connection to global news on the whole isn’t as robust as it used to be. I consider this beneficial. However, a consequence of this retreat is that I miss peripheral events most people would consider inconsequential.

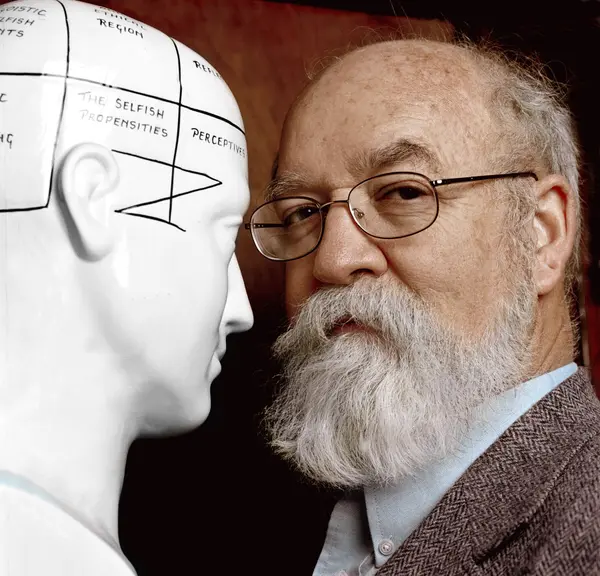

On April 19, Daniel Dennett died. For me this event is as far from inconsequential as anything could be. Dennett is by every measure one of my heroes. He was a titan of reason and ideas to whom I listened for hours at a time. I read his books, watched his debates and lectures. He both verified my intuitions and crushed my delusions. I will forever be grateful for Daniel Dennett. Shine on, you crazy diamond. My intertwined reading list over the last two months (in no particular order, akin to how I’m reading them):

Conan the Barbarian: the Complete Robert E. Howard Stories The Dawn of Everything by Graeber and Wengrow (my third rereading) The Sweet Spot by Paul Bloom Behave by Robert Sapolsky The Amulet by Roberto Bolaño The Dispossessed by Ursula K. le Guin (also thrice rereading) Merely Christianity by Robert M. Price The Silmarillion (my second time through) by JRR Tolkien The Heart of the Anarchist by Jaron Dagan “The gods of yesterday become the devils of tomorrow.”

- Robert E. Howard |

Archives

April 2024

Chrysalis, a growing collection of very short fiction.

That Night Filled Mountain

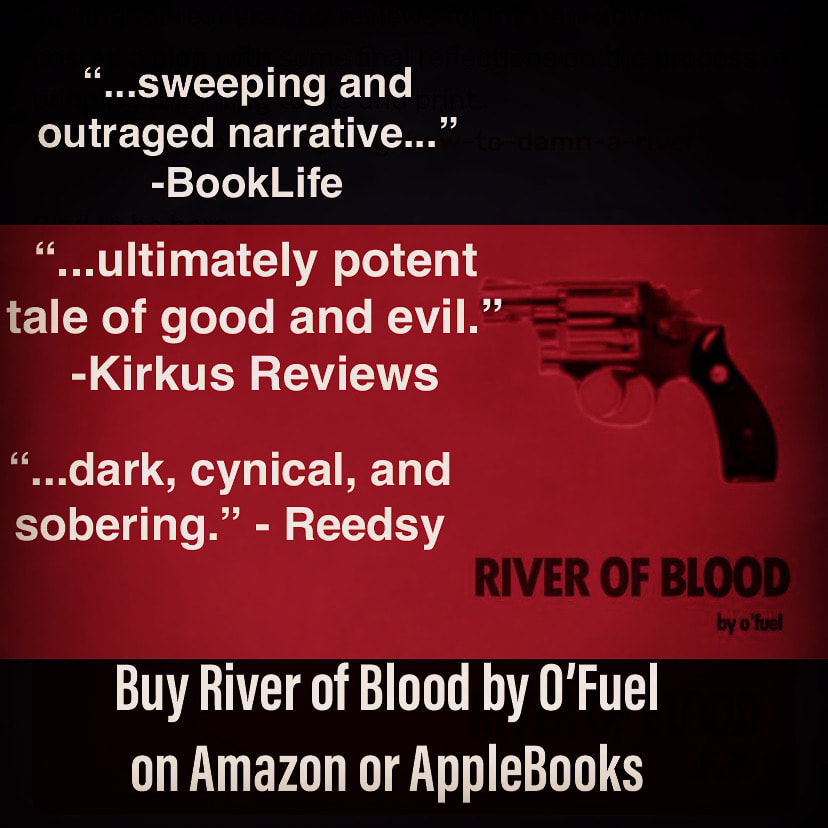

episodes post daily. Paperback editions are available. My newest novel River of Blood is available on Amazon or Apple Books. Unless noted, all pics credited to Skitz O'Fuel.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed