|

When I began work on my latest novel in progress,I felt sure of my direction and purpose but like any good work, it has challenged my ideas and shaken the foundations of some of my most ardent beliefs. What are we? Why are we? How are we? And does it matter? I call myself an anarchist for a myriad of reasons. Authority has never lived up to the means of its proponents. State authority has not stopped crime, war, or suffering. In fact, one can effectively argue that state authority is a champion of all these things. The state has changed the definitions of words like war. Government's promise of protection has never produced anything more than control and control stifles both political and individual freedom. We all want freedom and my goto answer for acquiring it is always individual autonomy. But does this autonomy even exist? Ironically, authority seems only workable in philosophically finite situations, ironic in that this is also the common argument against anarchism. “Anarchism only works in small, tight-knit populations.” Stripping state as an antecedent to authority leaves us with the few moments when authority actually makes sense, when it has tested well, such as reason and logic (both admittedly subject to limitations) which are the basis of one of the greatest philosophically robust of human inventions: the scientific method. When applied correctly, the simplicity of scientific method has rarely—if ever—led us astray. The weight of my newest novel balances on our lack of free will. The majority of scientific examination of free will reveals the murky world of intention and action as a sustained chain of cause and effect, not rationality and logic. We are not what we think we are--free will is an illusion. It seems no matter how we argue for free will, the argument against it is already ahead of the game, claiming any “choice” is a simple result of prior and present circumstances. The common wrench in any claim of authorship in personal choice is the philosophic question “Could one have done otherwise?” It is a diabolical little question. Prove that you could have or would have done otherwise if we could rewind time. Of course we can’t rewind time so the logical answer is always, you could not have done otherwise. Not all science agrees with the monolith of determinism. There is indeterminism, the idea that quantum mechanics brings to life the possibility of chance which seems to validate ideas of Epicurus in ancient Greece that “swerve” in the causal chain does actually exist. Yet folks like Einstien and Hawking and many other reject this thinking due to quantum decoherence: the macro-world is exceedingly stubborn to the averages of quantum indeterminism; any effect that the randomness of the quantum might have on classical mechanics is limited to say the least. Compatibilism is the belief that even in a determined world, free will (although not the classic metaphysical or religious concept of free will) is real and has a solid hold on our most important actions. Daniel Dennett is a champion of compatibilism. His work with the ideas of evitability and avoidance construct a world of choice that we can analogize to other parts of our anatomy and the universe at large. According to Dennett, the very complexity of a determined system can give rise to evitable futures and free choices. In physics we see that hydrogen is one thing and oxygen is another. Together—in a certain combination—they create another thing: water. Dennett argues that our minds are built with determined material in a determined system, neurons, synapses, cells, electrons, etc., none of which are free to do anything other than their assigned chores but the very complexity of that system produces our ability to choose. This is a tempting path. However, as I mentioned above, Dennett’s free will is not the free will of (most) religion and certainly not the free will required by anarchism based on personal autonomy. His is the world of avoidance mechanisms produced by biological creatures whose sole purpose is to live as long as possible within the context of procreation. Life learns to avoid death. That is not the style of free will needed to make political decisions. And of course base determinism still has the upper hand when it demands, once again, “Prove that you could have done otherwise.” Dennett once quipped that “ …we do have free will, but it’s made of tiny little robots.” And that very statement creates a problem for the style of free will one must possess to make a statement like, “I demand the power to choose my own destiny.” The growing catalog of data on the science of consciousness remolds what we consider free and willing decisions. What am I? I am a collection of biological cells working in tandem to keep the collective alive and on the move. A tragic irony in that eventually, without question, this collective will breakdown and cease to move. However, a reciprocal question comes to mind, “If my destiny is determined by the arrow of time and the piggybacked causal chain of events, in what political sense should anything but time and that chain have any say in my destiny?” Studies on behavior in light of a lack of free will might reveal cracks in the notion of determined free will and these studies bother Dan Dennett, myself, and others for good reason: science. Here is a quote from John Horgan in his article “In Defense of Wishful Thinking” in Scientific American: A recent experiment shows that belief in free will has measurable consequences. The psychologists Kathleen Vohs and Jonathan Schooler asked subjects to read a passage by Francis Crick , co-discoverer of the double helix, that casts doubt on free will. Crick wrote in The Astonishing Hypothesis (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993) that “although we appear to have free will, in fact, our choices have already been predetermined for us and we cannot change that.” Subjects who read this passage were more likely to cheat on a test than control subjects who read a passage about brain science that did not mention free will. Mere exposure to the idea that we are not really responsible for our actions, it seems, can make us behave badly. These types of studies seems to show that at the heart of the matter, we actually choose our actions based on punishment and reward. Horrifying, right?

Not so fast. A "belief in free will" is not proof of free will. No more than "belief in God" proves the existence of God. (Thanks to Dan Dennet) “Could one have done otherwise?” Could the subjects taking those tests have done otherwise without the statement about the possibility of our lack of free will? Could Timothy McVeigh have done otherwise without the inference of government intent on destroying the American way of life? Could the hijackers on 9-11 have done otherwise had they not been conditioned in the belief of a glorious afterlife? Could Robin Williams have done otherwise had he not know that his heart surgery carried the possibility of heavy depression? To what I am slowly coming to grips is the fact that possibly one of the greatest arguments against political control over the individual is the idea that government is not and never will be as complex and precise as the biology of life. If time and causal trajectory are my rulers then so be it. If 2+2 must in practice equal 4, so be it. But no gang of power hungry pawns in the systems of irrational political control should or could ever control me. Personal autonomy still has legs. It still breaths life. Not from the lungs and structure that I once envisioned for it but it is still viable and coherent.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Chrysalis, a growing collection of very short fiction.

That Night Filled Mountain

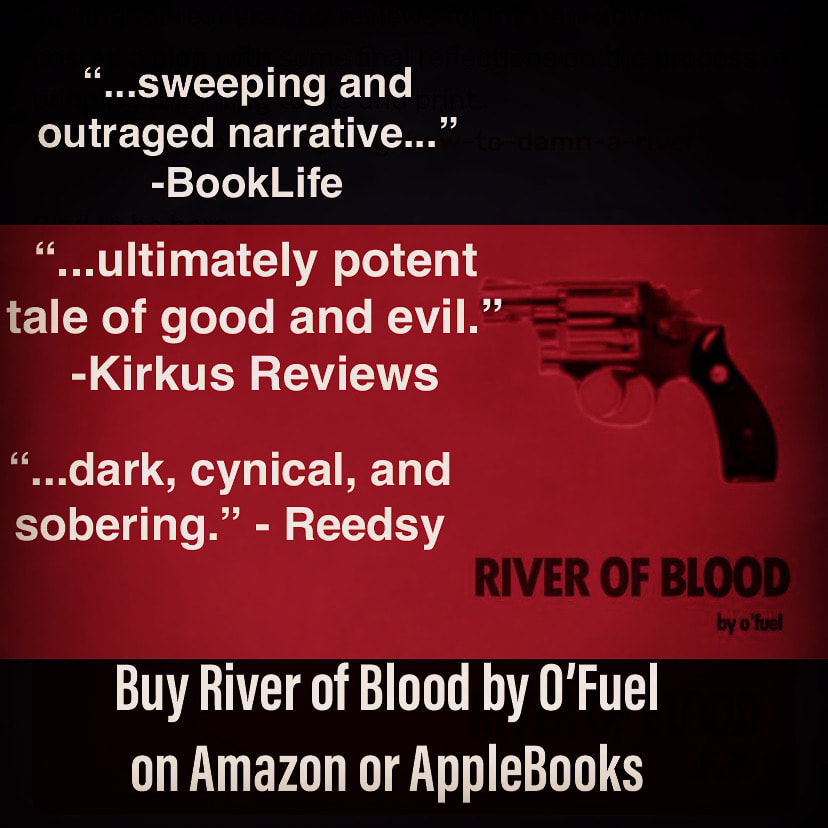

episodes post daily. Paperback editions are available. My newest novel River of Blood is available on Amazon or Apple Books. Unless noted, all pics credited to Skitz O'Fuel.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed